Hello Spain par le Dr Leroy Johnson

Good Bye America, Hola Spain

Good Bye America, Hola Spain

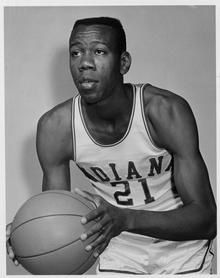

Leroy is 18 years

In November of 1961, after three years of studies, I left Indiana Univeristy and the United States of America. I shall always remember the cool and quiet last autumn morning, when I said good bye to a few of my trusted friends and travelled to New York City, where I would soon embark for Tangers on the Bovec, a Yugoslavian freight. X, a young Irish American woman and my best friend, started to cry, when I took my two suitcases from the truck of the taxi cab that had taken up to the bus station. X and I, students in the same courses, had eventually become lovers, in spite of the social pressure that should have kept us, a black athlete and a white co-ed, apart. After I had been kicked off the basketball team; joined and quickly been discarded from the US Army; and then returned to Bloomington, where I was determined to finish my studies, although I had no money for pay for them, X had remained by by side through all my trails and tribulations. In fact, this tall, long legged woman with light brown hair, greenish eyes, and a seductive smile, was the one constant in my very unhappy life; and during my last and painful year at indiana University, I would have fallen apart without her moral support and affection.![]()

X was one of the most courageous and morally upright persons I have ever known. Even now, at the beginning of my 69th year of life, I still marvel at her refusal to surbordinate her principles to the dictactes of American socio-racial taboos. She and I had shared an off campus apartment after I had returned from the military and tried to resume my studies. For a while, our flat, in one of the rare buildings in Bloomington where black and white people could live together, became the sanctuary, where, if only for short respites, I found refugee from the prying eyes and wagging tongues that were all too willing to remind me of failure. And failed I had, because at the end of the 1960 basketball season, Coach MacCracken informed me that he did not think that I was the type of young man he wanted on his team.

Coach McCraken, a person of this times- as all but the visionaries among us, and they often become martyrs if they attempt to force society to deal with its contradictions- and no one blamed him for protecting his team. And if order to do that, he had instructed all of his players to be involved in political demostrations- and I had taken part in

X, a tall Irish American young woman from southern Indiana started to cry, when I took my two suitcases from the trunk of the car in which we had as I boarded the Grey Hound bus crying as the car pulled away from the curb demonstrations supporting

the Cuban people's right to decide choose the type of government they want, even it that government was Communist; I had participated in the

nascent Civil Rights Movement"s marches on the Indiana University campus and in the city of Bloomington. Coach McCraken, although he never

explicily prohibit his players from engaging in politcial activities, there was an unwritten rule against athletes taking part in any political event

outside of the Democratic and Republican parties, the two traditional and acceptable American political organisations. At that time, in the early

1960s, black American athletes were surpposed to be gratful that they were attending a major university, that is to say primarily white institution.

In those days, Indiana University, with a student population of nearly twenty thousand students-of whom barely two hundred were black Americans-

,was indeed a university that serviced white America. Most black American students of my generation were the victims of segregated education, from primary to secondary school. In the late 1950s, very few black Americans had thopportunity to attend university; and those who did, attended historial

black colleges; that is to say segregated colleges at which black Americansn had to attend because they wre prohited by law from attending America's white colleges and universities. theirNonetheless, and in spite of the ideological confilicts between the varsity basketball coaching staff and me, the three years i spent at that school were among the most imprtant ones of my life. There I discoveredx and began to read the works Flaubert, Malraux, Ernest Hemingway, Juan Jiminez, Frederico Garcia Lorca, Marx, Lenin, Richard Wright, James Baldwin. At Indiana University, I began to study ancient Greek tragedy,ancient and medieval history; and it was there, I met intenational students from Africa, Europe, and Latin America. At that university, located

on one of America's most beautiful college campuses, I also met and fell in love with X, an intelligent and political conscious Irish-American

student from southern Indiana. Se and I met in a 1959 Spring semester English Literature survey course. X had grown up in southern Indiana, and

was the second of two daughters of a very successful physician. Although X's father was a firm segregationist, who found support for his ignoble

political position in the Bible, she and I We, disregarding the social taboo that forbade a white woman from dating a black man, went to the theatre

together, studied together, and, lastly, fell in love with each other.

Bill Garett,(photo on right) my best friend among the Hoosiers

Coach McCraken, already having problems with the sponsors of the team because they believed that there were too many blacks on the team, really began to feel pressure, when X and I began to be seen together in public. Had I left X alone, all would have gone well for me, because I was one of the best players on the team-my stastics during my three years on the Indiana University basketball support my statement. And I must say that I am proud to have played on one of the best college basketball teams in the United States during the late 1950s and early 1960s. However, academics and socio-political issures soon became as imporant, if not more important, to me than basketball. I believe then and now that athletes should be part of society; that they should be concerned with the social, economic, and political activities of their society. I have always thought that black American athletes, because of their very visible position in America society, have the obligation to demonstrate a solidarity with the oppressed, black, brown yellow, or white in America and the world. And that way the reason I became active in The Young People Socialist League, a Troykist politcal party in which working class people, black and white worked tgether for a better society. With time and a more complex analysis of American society, j'ai mis un peu d'eau dans mon vin. But in early 1960s, I was young and idealistic; I did not undertand the socio-political and racial history of American society; lastly, and, eventually led to my demise, I did not undertand that American society had just begun to recover from the Macarthyism, the vile belief that considered everyone who pointed out the hypocrisy of American society to be Communist.

As my mind drifts back to the springtime of my life, I realise that my ignorance of American history was both my strength and weakness; it was a strength because, like most young people of any generation, I was convinced that society, that is American had I know how dangerously I was behaving, surely I would have ceased. But, then I really believed in the truth of the American principles my teachers had taught me in primary and secondary school. However, at Indiana University I would quickly and painfully learn that not every American mother's son- women, white and black, were excluded from politics in the early 1960s- had the chance to become President of the USA. It was lie, I learned, that American society was democratic and free. It was a racist and capitalist society; a society of which much its wealth had been acclumumated by the raw oppression of slaves, the displacement and genecide of the Amerindians, and by pitting working class people of different races and ethnic background against each other. But I believed then that we could change the world in a day, if only the good people- and I believe that most people of the working class were honest and good- would unite. Of course, I would learn that society is very diffierent than the ways it is described in books. Nonetheless, even today in the 69th year of my life, I still believe in humanity"s ability to create social, political, and economic institutions that serve all of humankind, regardless of race, color, religion, and social status.

I was very sad and depressed When I fluncked out of college. More importantly, I felt shame and guilt. After all, athough I was not reared in my biological family, I was the first of this peasant family to attend university. And even then, though I did not understand full power of American rasism and class divisions, I was aware that my presence at Indiana University was unusual. And I was sad and depressed when I board the Bovac, the Yugoslavan freight that took me to Europe, where I would remain in a self imposed exile for over eleven years, first in Spain, and then in France. Fourteen days later, the Bovac put in at the port of Tangeirs.

Aboard the ship, I truly thought I was going to die from la maladie de mar. But I survived, and one early bright morning I saw the white falaises of Tangiers. What a beautiful sight to see for a "peckno" from Indiana. When I disembarked, I became aware of sounds and ordors unknown to most Americans. I was in an Arab and Muslim country. I had no idea of the cultural cleavage separating me from that society. All I knew then was that I was a stranger, not because

I wa black, but because I was a Westerner, a nominal Christian, and an American. However, I must say that the latter fact made things rather easy for

me during the two days I spent in that part of the world.

Soon I boarded a ferry leaving Tangiers for the Algercias, a sleepy and small fishing village on the southern coast of Spain. When I arrived at Algercias, I

had only ten American dollars in my pockets. Ansd for a moment, I began to think that my friends, including Walt Bellamy, had been correct. They all had

wanted me to try out for the new teams in the NBA. But I had had enough of of dictatorial basketball coaches, who told you what time to go to bed, who

wanted to control your social life, and who were anti-intellectual. No, I told all of them that I was going to Europe. Why Europe, one might ask. Well, I

am a product of late the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s. During that period, Europe, especially France, was the place to which the political, intellectual, and

social misfits in American society fled. Richard Wright, Chester Hilmes, and James Baldwin had found freedom in France. And I, too, young and naive,

believed that I could start a new life in Europe.

From the port of Algercias, I picked up my two suitcases containing all of my worldy belongings, and found the way to the train station. I was going to Madrid, where two young men whom had know at Indiana University were living; and with the aid of a Puerto Rican in the American Air Force, I was able to purchase a one way ticket for Madrid; I boarded the train and sleep though the night, and early the next morning I arrived in the Spanish capital. I spent one of my lasting two remaining dollars to rent two containers at the train station in which I left my suitcase; and then I asked directions in Spanish- luckily,

I had studied Spanish in both secondary school and university, and was therfore able to converse with the Madridlanos- for the American Embassy. I walked the long distance from the train station to the embassy; and when I arrived there, I went in and asked the authorities for the address of my two Ame-

rican buddies. To my surprise, the authorities told me that they could not disclose their address. However, they informed me, they would give me their

telephone number. I took my friends' telephone number that one of the Embassy officers had written neatly on a sheet of paper. The officer, a young white

American woman-who, I later learned was from California- must have known that I was in dire straits; and as I was leaving the Embassy, she followed me and told me how to reach the area of Madrid in which they lived. In fact, she directed me to the subway and told me what line to take, and told me at which métro station to descend. I thank her and headed for the métro. About twenty minutes later, I emerged from the Madrid métro, found a telephone booth, and call my friends.

The phone in their apartment rang six or seven times. I began to panic because they were they only people I knew in Madrid. What was I going to do? I

did have any money, and I had only purchased a one way ticket to Europe in my desperation and determination to leave America. Now I wa all alone in a

beautiful but strange city, thousands of miles from Indiana, from America. Finally, Doug, one of my two American friends in Mardid, picked up the telephone. LeRoy, where in the hell are you?" he asked. I told him the name of the métro station near the telephone booth, and ten minutes later he stopped his car in close to the métro station of which the name I had given him. Dave, his roommate and the only other person I knew in Madrid, was with him. We shook hands, and laughed. "Hell, LeRoy, I thought you'd be playing AAU basketball, waiting to be picked up by some NBA clubs. I never believed that you would come to Europe." Told him that I had to leave America; that I was too angry to remain there; that if I hadn't left, something terrible would have happened to me. "How did you get the draft board to let you leave the country?" David wanted to know. For a moment, I was silent; and then I replied: " I joined the Army, hoping that I would be stationed in Europe. But those Texas crackers started messing with me at Fort Hood; and when I got to Officer's Training School at Fort Benning, I knew that I could defend people who made me sit in the back of the bus. No, man, I just couldn't deal with that shit anymore. So I got out of the Army."

"How in the hell did you do that?" asked Dave."I informed the Company Commander that I would not fight for a country that treated me as an inferior. I told him that they could put me in prison, but that I would not remain in the military. So eventually they gave me a General Discharge under honorable condition. Shit, I didn't care what type of discharge I got because I couldn't remain in Georgia."

"I wish I could say that I know how you feel.I can't...but you do know how we feel about that shit, LeRoy, don't you?"

Doug and David, two white Americans, were among the true friends I had made during my years at Indiana Univeristy. During my last year on IU's basketball team, they, unlike most of my black as well as white acquaintances, did not abandoned me when I had become persona non grata , when it became abundantly clear to all and sundry that my days at Indiana university were numbered. The two of them, several international students, and the network of Jewish students of which I was a part, helped to traverse this difficult period. But at the end of my third years at IU, I left the school. The stress, emotional, and psychological destruction of that milieu were taking it toll on me. I could no longer sleep, my performance of the basketball court had greatly diminishes, I was unable to concentrate on my studies, and I began to suffer from mygraine headaches; headaches that incapacitied me for two or three days at a time. Though young strong, angry, and naive, I was exhausted; to save both my sanity and health, I decided to flee American society. But before and during my flight, I promised myself that I would return to fight the same injustices and inequalities that had won this first battle. No, even then I know that I had not lost, but rather I had the Exterminator's mentality: I would return to the USA, when I had acquired the education, after I had gotten the intellectual tools and experience to analyze and eventually to join the ranks of those Americans, black and white, working class, and bourgoise

Dr Leroy Johnson

copyright legendedubasket septembre 2006.

photos with the courtasy of Bradley Cook of Indiana University

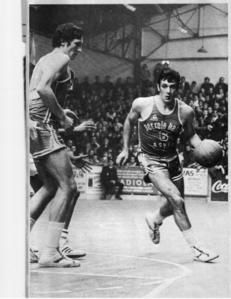

Leroy arrivera en Espagne, et s'entrainera avec le Real de Madrid sous la direction de l'homme d'alicante, le dénommé Pedro Ferrandiz.

Il rencontrera Wayne Hightower , un de américains aussi pionnier dans le basket espagnol.

Leroy finalement signera à Picadero Barcelone, aujourd'hui disparu.

Après une saison à Picadero, il signera au grand ABC Nantes et commencera son périple en France..

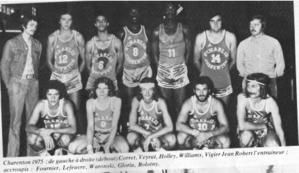

Après Nantes et ses grands techniciens comme Michel Leray et Raphael Ruiz (photo ci dessous) , ce sera l'un des nombreux clubs phares de la banlieue parisienne: le SCA Charenton.et ses roumains Borgescu (n°6) et Mihalecu, (n°11) réfugiés lors du tournoi d'été (voire photo, (avec accord Musée du basket))

Il y sera entrainé par Jean Robert (photo ci dessous, debout à droite, en 1975)et sera un bon copain à jJacques (Jacky) Renaud;

LJacky Renaud, lui-même devenu grand coach français durant les 80's et 90's (PUC, Stade Français et Hyeres Toulon).

Michel Leray sous le maillot de l'ASVEL en 1972

Qu'est devenu le Caen BC aprs le départ de Leroy?

Le CBC a continué sous la direction de Claude Trehet, son grand président, à tenir bien sa place parmi l'élite.

An 1973, quelques joueurs ayant bien connu Leroy comme Alain Chausy, Charles Tassin (Alsace de Bagnolet), Hauguel posèrent pour la photo, avec le coach espagnol, José Gasca. (photo ci-après)

![]()